My colleague Ernest DeFilippis tells what he’s learned on this important subject, and what he’s able to teach other men in Aesthetic Realism consultations.

My colleague Ernest DeFilippis tells what he’s learned on this important subject, and what he’s able to teach other men in Aesthetic Realism consultations.

Husbands all over America will feel strong, kind, and intelligent when they learn from Aesthetic Realism that 1) the purpose of marriage is to know and like the world; and 2) the biggest mistake a husband makes is to think that because a woman has consented to marry him he now owns her, and therefore doesn’t have to try to know her and the world she represents. In his 1950 lecture Mind and Husbands, Eli Siegel explains:

The first thing a man should think about in thinking of a wife, is whether he knows the person he’s thinking of as a wife….Men are conceited and can decide they know a woman. Besides, they can think knowing isn’t so important—it’s important to make a living, find out about sex, be aware of health, but knowing is a luxury.

A woman, without knowing it, most wants that she be known. I say this definitely. There isn’t a woman who doesn’t resent a husband’s not wanting to know her….The word know is a very deep word, but that doesn’t mean it is any the less an emergency word….Husbands think that once they have seemed to capture a woman, that is all. [TRO 634]

When I proposed to Maureen Butler in December 1987 and she said “Yes,” I was thrilled, and enormously grateful to Aesthetic Realism for what I had learned about love. But more than I knew, I was also doing what Mr. Siegel described: feeling now that she had said yes, I had captured her.

One of the ways this showed was in how I told the good news to people. As I would announce, “I asked Maureen Butler to marry me and she ACCEPTED,” it was quite apparent to my friends that I gave a certain smug emphasis to the word accepted. And though I was very happy, I had an uneasy feeling, which I didn’t want people to notice. I hope every man about to get married can learn what Ellen Reiss explained in an Aesthetic Realism class.

“Accept is a big word,” she said; and as she continued, I was seeing that I had made the acceptance of my proposal equivalent to a total acceptance of me. “Do you think,” she asked, “that while Ms. Butler accepted your proposal, you feel at ease with the idea of spending your whole life trying to deserve being accepted by her?” “No,” I answered. And she said that if Maureen seemed to “accept” me entirely she would be insulting me, because I knew there were things about myself one shouldn’t be for.

“I like the idea,” I responded, “of trying to deserve being accepted—more than I ever did. But spending my whole life doing it—that’s a long time.” Ms. Reiss explained that if we don’t feel we’re trying to be worthy of something so big and beautiful as deserving the love of a person, we won’t like ourselves—that’s true both for man and woman. And she said something I feel enormously grateful for:“Your danger is to feel that because your proposal has been accepted by Maureen Butler, you’re all clear….I see this as a beginning for you, not ‘And they all lived happily ever after.’” And with humor and encouragement, she added, “So we’ll all live happily-and-self-critically ever after.”

That was 36 years ago; and I love Ellen Reiss for what she taught me then and later. It has enabled me to change and keep changing in ways I have so much hoped to; it has enabled me to be a better person and husband.

I have seen that for a man to get the esteem and love of his wife, and his own self-respect, he needs to encourage her largest desire: to like the world itself. This necessary purpose is good will—which Mr. Siegel defined as “the desire to have something else stronger and more beautiful, for this desire makes oneself stronger and more beautiful”—and because of it, I have sweeping feeling for my wife, which grows more with every day.

The Fight Between Knowing And Conquering

Aesthetic Realism is tremendously kind and new in explaining that the mistake men make in marriage begins with how we see the world. Very early, I came to feel the world was a confusing mess, an enemy I either had to get away from or had to defeat by making it subservient to me. For example, as the firstborn son in an Italian-American family, I felt that my mother existed to serve me and that all I had to do to please her was permit her to do things for me, welcome her attentions—sit patiently, maybe even smile, as she dressed me, combed my hair, brought my food.

But while I felt kingly, I also felt dull and lonely, often preferring my own company. I didn’t see, as I was to learn from Aesthetic Realism, that my painful feeling of separation from people, which increased as I got older, was the result of my conceit—my thinking other people weren’t good enough for me. And I didn’t see my mother, Ida DeFilippis, as having feelings that were as real and meaningful as mine; I didn’t see her as a person with a critical mind, who was hoping to be understood. This inaccurate, really cruel way of seeing her continued with the women I later dated. In another lecture, Aesthetic Realism Looks at Things: Love and Home, Mr. Siegel was describing what occurred with me when he said:

Since [men] have seen their mothers as caressing them, taking care of them, and being nice to them, with all their talk of emancipation, that is the way they want to see women from then on. [TRO 391]

I thought a woman should be thrilled that I showed even the slightest interest in her, that I looked at her, spoke to her, asked her out. I thought these attentions showed my deep feeling, and that a woman should fall into my arms in gratitude. If a woman didn’t succumb to me, I’d feel insulted and try to soothe my hurt ego by scornfully dismissing her with “Who does she think she is?!” or I would try to break down what I saw as her “front of indifference” by flattering her. When I did get a woman’s approval, I’d puff myself up thinking, “I really got it!” But whether I felt humiliated or triumphant, vengeful or self-congratulatory, one thing persisted: my thought was essentially about me. My mind could not take in the feelings of people, objects, the world I was born to know and like. I felt an aching unsureness and disbelief in myself, and an icy hardness as to people that made me very ashamed.

When I think of how boorish, mean, ludicrous my notion of love was, and the magnificent education I received in classes taught by Eli Siegel, I consider myself one of the luckiest men who ever lived. In one class, at a time when I was angry with a woman who didn’t give me the utter approval I wanted, Mr. Siegel asked me with critical humor, “If you were a woman, would you be entirely in love with yourself?” “No,” I answered. Continuing, he said:

There are two kinds of love: 1) the kind we definitely, deeply work for; and 2) the kind of love about which we think that because we are we should be loved. The second has predominated with you….You got your mother’s love very easily; and that idea of love without working for it is still with you.

And he said with beautiful, utter conviction:

The love you don’t work for isn’t worth a damn, according to Aesthetic Realism!…I’m being very careful. Everything in love, you have to work for. I don’t think you believe that, Mr. DeFilippis.

E. DeF. I don’t think so either.

What I saw then as drudgery and as an interference to what I wanted, I see so differently now. The work Mr. Siegel was encouraging in me was the pleasure of using myself, body and mind, to know a woman and strengthen her—to have good will. It is work that makes me happy to wake up in the morning and greet the new day with Maureen; to anticipate with excitement a conversation we may have; to be affected by how she sees—perhaps something in the news that day, or in a book she is reading. I am grateful to her for encouraging my mind, including a greater love for literature—for example, Henry James, François Mauriac, Sir Walter Scott, novelists she cares for. And as she has spoken about people who are suffering from the injustice of economics in America, and we have written articles and letters about how Aesthetic Realism explains the cause, and about what will have our nation kind, the luscious respect I have for her has grown. I’m so glad that as I hold her, look into her eyes, am stirred by her body, my thought about her is stirred too: I want to see more fully who she is. I tell you this: Mr. Siegel was sure right when he said, “The love you don’t work for isn’t worth a damn!”

“Eager Interest” versus Unkind Complacency

In Mind and Husbands, Mr. Siegel speaks about what it means to know the person we’re married to:

No woman should ever sum up a man, or any man ever sum up a woman. When that is done the human spirit screams, though the scream is not heard….Knowing is knowing, nothing less. It means that what goes on within the woman, what her relations are, what she hopes, what she fears, what she doesn’t know she feels, should be a subject of eager interest for the husband. [TRO 639]

Aesthetic Realism can have men see the mind of woman as a subject of “eager interest,” as what a man proudly needs to complete himself. So husbands now sitting across the dinner table from their wives have had a fear of and contempt for the inner life and complexities of the women they married. Husbands have seen a wife’s complexity as interfering with our comfort, disturbing the haven from the world we have wanted marriage to be. In the process, husbands have welcomed boredom, stifled our own minds, made ourselves unlovable. Men have wanted to see the best thing in a woman—her desire to know and understand herself and others, which can have unsureness and confusion with it—as a sign of weakness, and we have dismissed a woman’s depths with what Mr. Siegel described as the “Oh, sleep it off darling; it will be all right in the morning’ attitude.” This attitude, he said, “has insulted women for centuries;” and it always makes a husband despise himself—because the best and truest thing in him doesn’t want it.

I remember, with regret, a time when I was annoyed by a worry Maureen had about an old friend, who was ill. During a discussion about marriage and ethics in an Aesthetic Realism class, I commented, “Ms. Butler gets into a drama about her friend,” and Ellen Reiss asked me, “Do you think when you don’t understand people you get angry?” “Yes,” I answered. And she said, “To try to have the people one had to do with early be in one’s mind in the best way is not a ‘drama’: there is something Ms. Butler needs to think about.” To have my thought more honest and kinder Ms. Reiss suggested that I “write about what it would mean for Maureen Butler to have good will for her friend.” I did, and it had an immediately good effect on both Maureen and me.

From an Aesthetic Realism Consultation

I love teaching what I’ve learned to men in Aesthetic Realism consultations, men I respect very much, like the man I’ll call David Gerard. In one consultation Mr. Gerard, married three years, spoke about having gotten angry with is wife, Ann, because she “surprised him,” as he put it; that is, she didn’t see a particular situation the way he assumed she did. He was ashamed of his anger and wanted to understand it.

We asked him “Do you think one of the classic mistakes husbands make is, they think they own their wives and therefore know them?”

David Gerard. I can see that happening very easily.

Consultants. Has it happened?

Mr. Gerard laughed affirmatively. And we asked, “Does Ann Gerard confuse you?”

David Gerard. Sure she does.

Consultants. Is it happily confused? Is it, “Yes, she confuses me, but I want to know more,” or she should just see things your way so everything is nice and smooth?

David Gerard. I think it’s both.

Consultants. Do you think men have given the message to their wives, “I don’t want to be bothered by how complex you are”?

David Gerard. Yes.

Consultants. And then a situation may come up and a man can feel, “How dare she cause me to have to think!”

Mr. Gerard nodded. He was seeing he had not wanted to think about why his wife felt as she did. We asked him: “Do you think you have complacency?” “Complacency?” he responded. “Yes, complacency,” we said, and gave an example: Did Mr. Gerard think there was complacency in his saying earlier with a quality of complaint, “I don’t know how to ask her questions sometimes!”

David Gerard. Now that you say that, yes.

Consultants. Do you think men want to see themselves as complacent?

David Gerard. No.

Consultants. Right. What we tell ourselves is that “I’m doing a hell of a good job under tough circumstances trying to understand her, and she should be grateful without limit!” Should we say, “Mr. Gerard—he’s a good guy. Give him a break. What more can you ask”?

“No,” said David Gerard, relieved, “I don’t want that.” He laughed seeing how ridiculous and arrogant it is to think we know a person, when a person is—as Mr. Siegel described—the most complex form of reality. And we said: “Ann Gerard may surprise you again….The whole world is in her. This is the beautiful thing Aesthetic Realism teaches.”

A Wife Stands for the World

In Mind and Husbands Mr. Siegel says:

We marry people, and a person happens to have millions of blood cells and hundreds of aspects. We marry complete representatives in miniature of the flourishing universe. We don’t marry consolations. [TRO 638]

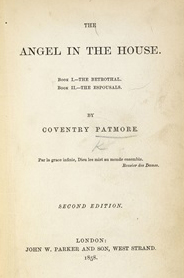

We can see an illustration of this great idea in a poem I care for very much. I learned of it in the Aesthetic Realism Explanation of Poetry class, taught by Ellen Reiss. It is The Angel in the House, by the nineteenth-century English poet Coventry Patmore. This long poem composed of many short poems was published in parts between 1854 and 1862, and Patmore dedicated it to his first wife, Emily Andrews.

We can see an illustration of this great idea in a poem I care for very much. I learned of it in the Aesthetic Realism Explanation of Poetry class, taught by Ellen Reiss. It is The Angel in the House, by the nineteenth-century English poet Coventry Patmore. This long poem composed of many short poems was published in parts between 1854 and 1862, and Patmore dedicated it to his first wife, Emily Andrews.

He describes the meeting, courtship, wedding, and marriage of a man and woman. Clearly, the husband stands for Patmore himself, and throughout there is a desire, ever so thoughtful and passionate, to see who this woman is and be worthy of her love both before and after marriage. He wants, he says, to “always seek the best for her / With unofficious tenderness.” That is good will, and he sees it as the same as love for her and taking care of himself.

In a poetry class titled “Can Men and Women Understand Each Other in Poetry and Out?” Ellen Reiss discussed “The Married Lover,” one of the poems in this collection. Its first line is: “Why, having won her, do I woo?” Said Ms. Reiss:

It is a good poem and it says something very important. It is about the fact that he has this woman, who is his wife—he has her in every way, including body—and yet he feels still there’s something he has to keep pursuing which he’ll never have….And the large thing is, he’s happy about it.

The first four lines are:

Why, having won her, do I woo?

Because her spirit’s vestal grace

Provokes me always to pursue,

But, spirit-like, eludes embrace.

There’s something in the way she sees the world,” said Ms. Reiss, “that makes him feel he has to keep trying to find out about it.” These lines are against a husband’s smugness and complacency—that feeling, Now that I’ve won her she’s mine and I can see her any way I please!

Patmore feels that there is something so large in his wife it cannot be embraced, that even as he touches her there will always be a sense of awe. He writes:

… yet so near a touch

Affirms no mean familiarness.

“Mean familiarness,’” explained Ellen Reiss, “is a Victorian way of saying contempt.” And she asked, “Can you have touch and not have ‘mean familiarness’? It is a question agonizing men and women all over America right now.” I’m tremendously thankful to be seeing with Maureen how sex can make for respect and pride.

There Are Touch and Respect

On the subject of touch and respect—I comment on a stanza I love from an early part of The Angel in the House. It counters a mistake husbands make: not seeing their wives as a oneness of mind and body, and seeing sex as in a separate world, unrelated to anything else. Patmore writes:

I drew my bride, beneath the moon,

Across my threshold; happy hour!

But, ah, the walk that afternoon

We saw the water-flags in flower!

The first two lines are about sex. There is a feeling of intimacy and width, of passion, as he carries her across the threshold and then—”happy hour!” But the feeling in the last two lines is continuous with that happening and has, if anything, even greater release and delight—and it’s about their seeing the outside world together: But, ah, the walk that afternoon / We saw the water-flags in flower!

I respect Coventry Patmore, and he has had me love and value Aesthetic Realism more. “The Married Lover” ends this way:

Because, though free of the outer court

I am, this Temple keeps its shrine

Sacred to Heaven; because, in short,

She’s not and never can be mine.

Ms. Reiss explained that Patmore is saying: “I’m close to her—I’m not in the outer court anymore—but I do not own her; ‘She’s not and never can be mine.’” She said of the poem: “It’s a rather beautiful way of seeing, and it’s pretty unusual. And Aesthetic Realism can have it be in people’s lives.”

This is the joy and kindness men and women are yearning for. I conclude with sentences David Gerard wrote in a letter:

I am so grateful to be married, and in the midst of learning what it means to have good will for another person. I state flatly, this would not be possible had I not been soundly educated, as every man needs to be and deeply wants to be, through the Aesthetic Realism of Eli Siegel.

More on Aesthetic Realism as to love and marriage:

What Marriage Is Really For—issue #1915 of The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known. It begins the serialization of a lecture by Eli Siegel in which he discusses his tremendously musical poem “A Marriage.” In her commentary placing the importance of how Aesthetic Realism sees love and marriage, she writes:

The following central principle of Aesthetic Realism is true about love: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” That principle is philosophic—it is a landmark in the history of philosophy—and it is as practical as anything can be. It’s about people right now looking for love online; and about a marriage, rather dreary, after 40 years. It’s about people trying to act at ease about sex but feeling confused, angry, and disgusted with themselves. And it’s about why the relation of Romeo and Juliet is beautiful. The 1930 poem “A Marriage” embodies the principle I just quoted, embodies it logically and also throbbingly, sweepingly. In the poem we see and hear the opposites: the intimacy of love, so personal, and also the width of things. And in it, in the statements and music, we feel too mind and body, closeness and intellect, touch and that hero of the poem, “a word.”

Aesthetic Realism and Love by Eli Siegel